The Student Guide to Playwriting | Characterisation

Wed 03 Feb 2016 |

Playwriting

The Student Guide to Writing: Playwriting is the first in a new series of competitions designed to share the best creative writing training with students and teachers at schools, colleges, Universities and elsewhere across the UK. You can find out more about the scheme here.

LESSON PLAN: CHARACTERISATION

BY TOM HOLLOWAY, PLAYWRIGHT AND MENTOR FROM THE BUSH THEATRE

This lesson will be focused on the development of character. We will look at what character means, why it is important and how it is an essential part of any piece of theatre, even when on first glance it might seem absent.

The exercises in this lesson will help you build an entire life for a character before the point of time the play takes place and during it.

Another thing we will look at, and an element of writing I firmly believe in for all stages of creating a play, is the importance of not editing in your head, but getting the work on the page. It is only once it is on the page that we can really judge it and develop our work further. The exercises I suggest are about writing quickly and writing a lot, and then reflecting on what has been written later.

WHY THIS AREA OF CRAFT IS IMPORTANT.

CHARACTER’S RELATIONSHIP TO PLAYS

Before we can talk of the importance of character we need to look at some essential elements of a play. There are two things every play must be about:

i) People

ii) Conflict

Whether it is Beckett, Kane, Albee, or Miller, every play that has ever been written has these two elements at their core. The works that seem almost devoid of narrative (although I dispute that any work is truly devoid of narrative), still have people and conflict sitting at their heart. If you are writing a play with two penguins on stage, you are still writing about people and conflict.

This means that character is one of the two essential elements of playwriting, and so a piece of theatre cannot exist without it.

Whether you give your characters full names, simply letters for names, or no names at all, you still need to develop them as fully conceived humans (even if in the form of penguins) with flaws and strengths and desires and fears.

CHARACTER’S RELATIONSHIP TO STORY

The next thing we must look at before developing our characters, is the most basic story structure that exists. Not only is this the most basic story structure, it is also in fact the structure of every story that has ever been told:

i) A character exists in an environment

ii) They want/need something

iii) Something or someone gets in the way of what they want

iv) They either succeed or fail in getting what they want, but they learn something along the way.

From Gilgamesh to the works of Charlie Kauffman, this structure holds true. Most questions are asked about ‘iv’. Some say ‘but what if the point is that my character hasn’t learnt from their mistakes?’ The major thing to remember is that your character must be different at the end of your play than the beginning. They must have gone on a journey. Even if this journey is a rejection of change, conscious or otherwise, they need to have been faced with something life changing during your play. Perhaps at the start they think they can change, only to realize they can’t or don’t want to. This is still a journey and still makes them different at the end to the beginning.

I would also say that the structure above should exist for every one of your characters, from your main character down to your smallest. The scale of what they want/need might be different, but to make them feel well rounded they still need a journey like this. A waiter might simply need to take another character’s order, but the character is too busy talking to someone else. The waiter then either succeeds or fails in getting the order, but they’ve learnt something about their skills, or the annoying nature of the customer, along the way.

Tom Holloway’s Forget Me Not, Dec 2015

CHARACTER’S RELATIONSHIP TO CONFLICT

And finally we must think about what conflict means to our character. I think a mistake we can often make as playwrights is that we give a lot of attention to the large conflict a character faces, but forget that there are layers of conflict, just as there are in every day life. In fact to go a step further, it is actually how our characters respond to small, everyday conflicts (having to wait for an occupied toilet… Trying to get a waiters attention… Running for a bus they’re not going to catch…) via which we can get a deeper understanding of the character’s main needs. How our character responds to just missing a bus will also tell us how they are coping with the cancer diagnosis they have just received, for instance. Continually placing our characters in situations of smaller every day conflicts lets us do the important job of showing and not telling. It also lets us map the journey of our stories more, and also stretch time out before our characters come head to head with their main needs and the struggle to fulfill them.

A SIMPLE EXERCISE OR EXERCISES USING THIS CRAFT ELEMENT TO DEVELOP YOUR PLAY.

Before we start looking at these exercises, I’d like to request something of you. When you do these exercises, do them quickly. Give yourself perhaps a minute to answer each once. Set a stopwatch even. And simply follow the first impulse you have. Don’t think. Just write.

EXERCISE ONE: BUILDING A LIFE FOR OUR CHARACTER

For this exercise, choose one of the characters from your play you are writing. Remember, just write down the first thing that comes to mind. Don’t edit in your head. Follow your impulse. Editing can come later. Only to go up to the age that your character is at the end of their play for this exercise – this is important so you don’t spoil the sense of anticipation the end of plays often create about where is the character going to go next.

i) Write down one surprising feature of your characters birth. Were they born early? Was the labor long and hard? Were they born by Caesar section? Was the birth in a hospital or somewhere else? Was the baby in danger? Was the mother in danger? Did the mother survive? Was the father there? Etc…

ii) Write down one surprising thing that happens to your character from birth to age ten. Is it starting school and if so, what about it? Is it moving home, and if so what about it? Does a parent die, and if so what about it? Do the parents divorce and if so, what about it? Do the character make a friend and if so what about it? Etc…

iii) Write down one surprising thing that happens to your character from the ages of ten to twenty. Is it about them leaving school and if so, what about it? Is it about them losing their virginity and if so, what about it? Is it about their first job and if so, what about it? Is it about their first experience of alcohol/drugs and if so, what about it? Etc…

iv) Write down one surprising thing that happens to your character between the ages of twenty and thirty. Is it finishing university and if so, what about it? Is it about falling in love and if so, what about it? Is it about a first betrayal and if so, what about it? Etc…

v) Write down one surprising thing that happens to your character between the ages of thirty and forty. Do they get divorced and if so, what about it? Do they have a child and if so, what about it? Do they lose their job and if so, what about it? Etc…

vi) Write down one surprising thing that happens to your character between the ages of forty and fifty. Do they get sick and if so, what about it? Do they have an affair and if so, what about it? Do they travel and if so, what about it? Etc…

vii) Write down one thing that happens to your character between the ages of fifty and seventy (note the difference here, and I’m also not trying to say that not many interesting things happen to old people!). Do they retire and if so, what about it? Do they fall in love and if so, what about it? Do they get sick and if so, what about it? Etc…

viii) Now, if you haven’t already, write one surprising thing about your character’s death. Perhaps they died at an earlier age, or perhaps they have lived in to their seventies. Either way, did they die of sickness and if so, what about it? Did they die of an accident and if so, what about it? Did they take their own life or were they murdered and if so, what about it? Etc.

You now know something about the birth of your character, their entire life and even their death. Some of what you’ve written might seem to conflict with other parts you’ve written. This is good. This is what life is really like.

Now that you know all this about your character, write for one minute, and only one minute about your reflections on who you think your character is, what kind of person they are, their struggles and strengths, things like that. Again, don’t think, just write.

Tom Holloway’s Forget Me Not, Dec 2015

EXERCISE TWO: THE BEST AND WORST THINGS THAT CAN HAPPEN TO YOUR CHARACTER

We need to learn what our character wants and what they fear. This is about mapping the journey of conflict and effort for our characters. One danger in playwriting is that we jump too quickly to the major drama a character faces without necessarily earning that. This exercise should help prevent this.

Again write quickly. Write the first thing that comes to you. Do not edit in your head. In fact until you have a first draft of a script, you should NEVER edit in your head.

i) What is the best thing that could ever happen to your character? Perhaps they win the lottery, for instance.

ii) What is something that could make the best thing happens? They win the lottery because they bought a ticket.

iii) What is something that could make the thing happen that makes the best thing happen? They buy a lottery ticket because they were in a news agency and needed a pick-me-up.

iv) What is something that could make the thing happen that makes the thing happen that makes the best thing happen? They needed a pick-me-up because they just found out their partner was leaving them for someone much younger and much more beautiful.

v) What is something that could make the thing happen that makes the things happen that makes the thing happen that makes the best thing happen? Their partner left them for someone younger and more beautiful because they had spent years in a problematic relationship with someone they never should have been with in the first place.

Obviously your choices will be far more interesting than my examples.

i) What is the worst thing that could ever happen to your character? Perhaps they are fired from their job, for instance.

ii) What is something that could make the worst thing happen? They were fired from their job because they were stealing from the workplace.

iii) What is something that could make the thing happen that makes the worst thing happen? They are stealing from their job because they have a gambling problem.

iv) What is something that could happen that would make the thing happen that makes the thing happen that makes the worst thing happen? They have a gambling problem because of a mix of being prone to addiction and currently facing a lot of unhappiness in their life.

v) What is something that could happen that would make the thing happen that makes the thing happen that makes the thing happen that makes the worst thing happen? They are currently facing a lot of unhappiness in their life because they have found out their partner is cheating on them.

Tom Holloway’s Forget Me Not, Dec 2015

Through going through these two sets of steps (and ignoring my examples as much as possible!) you now know what is the best and worst thing that could happen to your character. This best and worst thing might not actually be your character’s biggest desires and fears, but they will definitely help you work out what those desires and fears are. For instance, in my examples, the first character doesn’t necessarily want to win lottery, but they do want to be out of an unloving relationship and be able to start their life again. And in terms of fears, my character’s biggest fear might not be losing their job, but in fact that their partner is cheating on them and they’re going to have to try to leave them and start a new life.

The other thing this exercise allows us to do is think about layers of conflict. If you think about my examples from the worst thing that could happen, my character might be sitting in the meeting where they’re losing their job, while also worried about the gambling debts they’ve incurred, while also worrying about their partner being unfaithful to them. If I was to try to develop this scene further, because these conflicts are already so big, I would think about smaller conflicts I can bring in to the scene. As well as all this does my character need to go to the toilet, while being told they’re fired? Is English their second language so they’re struggling to follow what their boss is telling them, all the while facing the worry of the gambling debts and the potentially unfaithful lover? Does the meeting with the boss keep getting interrupted by the boss’ secretary trying to get some signatures from the boss? How my character responds to these interruptions will tell me how they feel about being fired and therefore how they feel about the debts and their lover. If they’re avoiding coming to terms with the state they’re in, they might be fine with the interruptions, for instance.

FINAL ADVICE

A teacher once said to me that every character should always be ‘on the edge of disaster’. I love this term. Whenever you are developing your character, keep asking yourself this question, and if there are times they seem not to be on the edge of disaster, see what you can do to get them back there. And remember, there are small and large disasters. Don’t forget the small ones, and in fact use them to highlight the large one.

Also, although I have found these exercises useful at times, I also often don’t use them at all. I find my characters through putting them in scenes and seeing how they respond. One scene leads to another.

Find more lesson plans here.

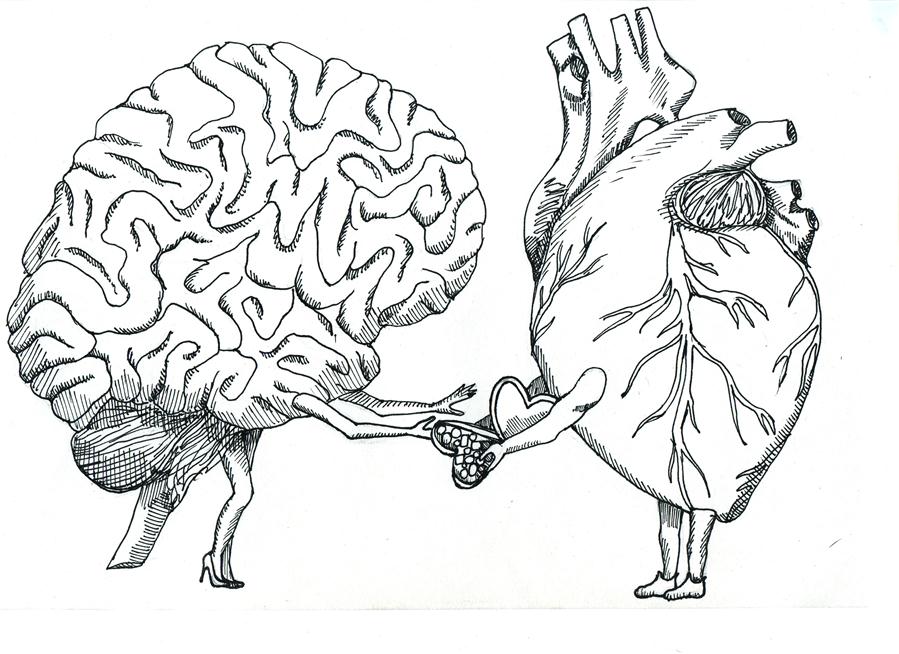

The brilliant illustration above is by Kelly M. Fritz.