A short historical background to the Magna Carta

Mon 15 Jun 2015 |

Our Plays, The Bigger Picture

On 25 May president of the Law Society – who are sponsors of The Invisible – Andrew Caplen delivered a speech on the rule of law at the Malaysian Bar Council and gave a brilliant explanation of the history of the Magna Carta. Today, as the country celebrates the 800th anniversary of its sealing, we thought we’d share it with you.

The Magna Carta

A short historical background.

Eight centuries ago, the English King – King John – had brought the English throne into debt and disrepute, particularly following an unsuccessful war against France. His barbarity, extortionate taxes and preference for ruling under the principle of vis et voluntas – or arbitrary ‘force and will’ had resulted in great discontent.

In the winter of 1214, rebellious barons led by Robert Fitz-Walter demanded that the King restore their rights and privileges. King John’s response was negative and on 12 May 1215 he ordered that their entire estates be seized.

On 17 May 1215, the barons reacted by marching on London, which welcomed the rebels and opened its gates in defiance to the King. Once King John had lost London, he sensed that perhaps it was time to compromise.

And that compromise was the Magna Carta. Also known as the Great Charter.

The two camps met at a place called Runnymede, a few miles west of London, chosen because its boggy ground made open combat almost impossible.

The Barons made their demands – 63 in total. King John did listen. He had little option to do otherwise!

Most of their demands only make sense in the context of their time. But some have proven to resonate across the ages.

Most famously – a guarantee to all free men that they would be protected from illegal imprisonment and seizure of property. That there would be access to swift justice and parliamentary assent for taxation. And further limitations as agreed by a new ‘Common Council’ of the realm. An early form of parliament.

King John agreed. He had no choice. In doing so, he was the first King to bow before the supremacy of law.

Lord Denning, a previous master of the rolls, referred to the Magna Carta as ‘the greatest constitutional document of all times – the foundation of the freedom of the individual against the arbitrary authority of the despot.’

Because, although the Magna Carta may have been written eight centuries ago, its words still serve to inspire people throughout the world, reminding all of us that the rule of law is the foundation of any truly democratic society.

Some of the clauses in the Magna Carta remain in force in the United Kingdom today.

Clause 39 for example:

‘No freeman shall be taken or imprisoned, or be disseised of his Freehold, or Liberties, or free Customs, or be outlawed, or exiled, or any other wise destroyed, nor will We not pass upon him, nor condemn him, but by lawful judgment of his Peers, or by the law of the land. We will sell to no man, we will not deny or defer to any man, either Justice or Right.’

And Clause 40:

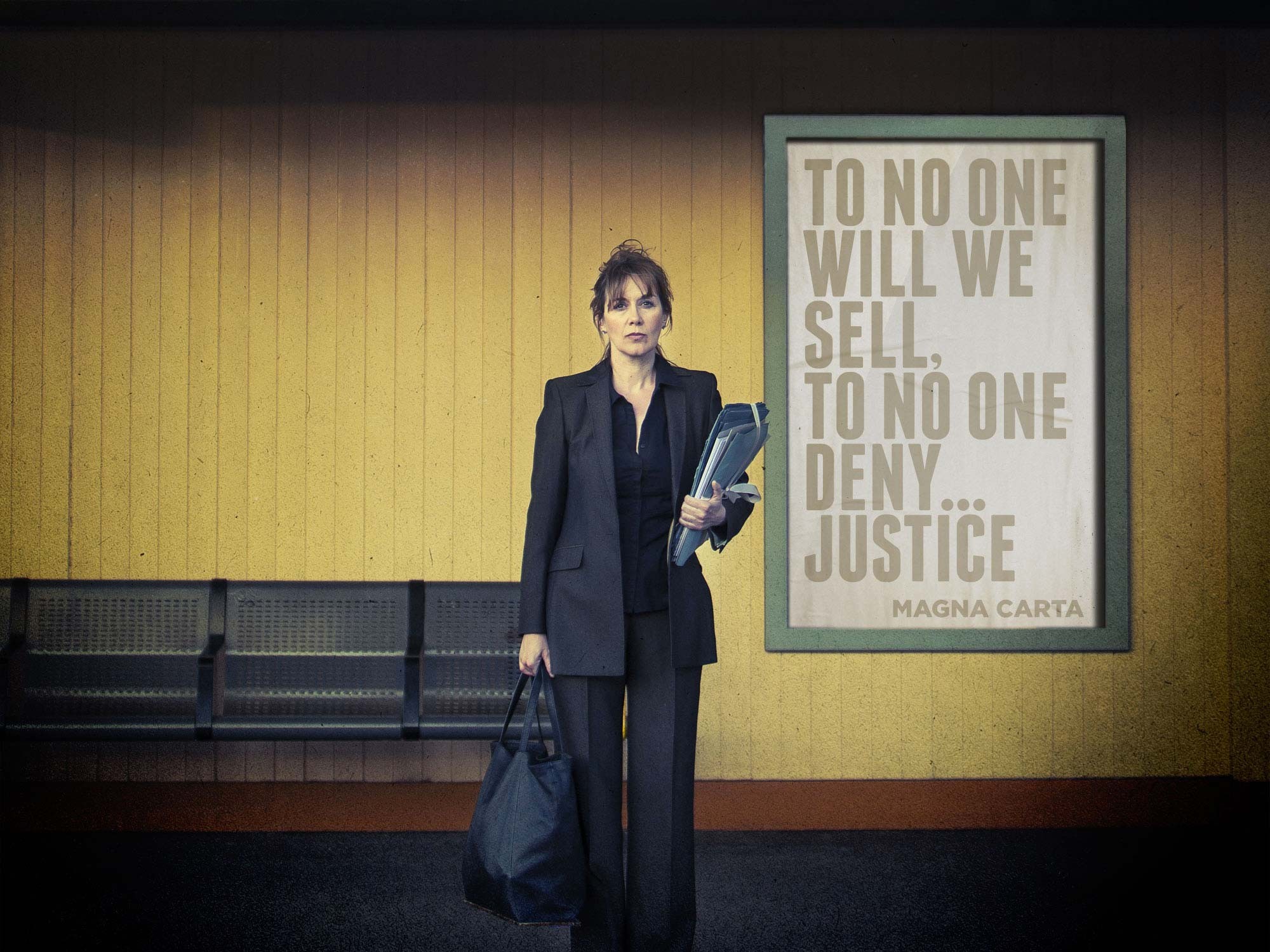

‘To no one will we sell, deny, or delay right or justice.’

The Magna Carta was a watershed moment in English law.

It cemented the idea that the law of the land should reign supreme, not the state. Once this concept was given credence, it proved impossible to revoke. That is why the Magna Carta is regarded as being the foundation of the rule of law.

Rudyard Kipling, a famous English novelist and poet wrote this:

‘And still, when the mob or monarch lays

Too rude a hand on English ways,

A whisper wakes, the shudder plays

Across the reeds at Runnymede’

The Invisible by Rebecca Lenkiewicz runs at the Bush Theatre from 3 July – 15 August. You can find out more about the play and book tickets here.

Or read Andrew Caplen’s speech in full here.